Text By: Carmen Bowes

Photos By: Samuel Taylor or as noted in text. Stock and historic images from US Library of Congress, Wikimedia, WVEXP and Austin Reid.

A part of me wants to say something cliché. “I’ve traveled far and wide and seen nothing.” Well, the remnants of something. A lot of empty places. I’d thought it was a West Virginia/rest-of-the-country problem. It isn’t. It is a rural/urban problem or a trendy/tired problem. It doesn’t seem to matter what state, what region, what big town is THE big town near you; past the burbs, the devastation is vast and real. A forgotten and forlorn America hiding in the recesses of the economy. Those people, the ones hiding, could give 2 shits about social issues. They are 1 of 50 people in a 100-square-mile space. My guess is, they can get along with those 49 people. The people hiding want to be hidden. They want to be left alone to farm or ranch or hunt or shoot assault rifles into the wide-open spaces or whatever thing it is that brings them joy in a poor, mundane world.

FIRST STOP

Downtown Richmond, Indiana

An odd girl is walking down the sidewalk in front of us. She is plump and, while adult-sized, is dressed like a child. She moves with insanity, sporadic and without purpose. We are wasting time wandering around a town called Richmond, Indiana while our pizza order bakes. The pizza shop had a former life as a bowling alley. The door still hosts a pin-shaped window. We walk. The girl stops outside of a chain-link fence, inside a cat rubs against wildly-unkempt shrubs. We cross the street like a couple of wimps.

Richmond is charming to me in the way that most sweet, old towns are. There are grand homes that are still lived in but could use some love. There are cobblestone streets and a couple restaurants still hanging on. There are old men mowing their lawns and bored young people looking for trouble. All the things my little town had.

We pick up the pizza and head to our campsite at a Kampground Of America (KOA) right off the interstate. This spot was chosen because it was convenient. In the future, fuck the amenities, serenity. The pizza is good and salty. Instead of triangular, pie-shaped slices, it is cut in a grid pattern. The bits around the edge take on an abstract, half-curved, and half-angular form. Mosquitoes come on heavy and the sound of trucks from I-70 blow past us through the thin tree line.

Old Reid Hospital - Photo Courtesy of Austin Reid, www.austinereid.com

Sitting in the dark, Sam’s face shines bright from the blue light of his phone. He is reading me an article he found about an abandoned hospital in Richmond, lovingly called “Old Reid.” It caught our attention on the way in and out of town, standing there massive and peculiar. Its tale is one of expansion and annihilation.

Its conception was the result of a large donation of $130,000 by John F. Miller. Construction began in 1905. Many additions took place over the years, the last in the 1980s. The need for more space was insatiable. Looking at the structure now, you can see all its appendages. The original building cut of stone, looming, and the most recent addition, a dark glass sheet of windows divided by gray concrete. Modern.

Old Reid grew beyond its own reach somewhere in the late 1990s and by the 2000s, it was clear that the hospital would have to move to a new facility. Cynthia Rauch was able to take a look around the space just before they chose to move and said this, “The building showed the history of medicine and not the future of healthcare.” From 2004 to 2008, the branches slowly moved out and finally Old Reid sat empty for the first time in nearly 100 years.

Old Reid Hospital. Photo from Library of Congress

Shortly after its closing, an investor bought the property just in time for the financial bubble to burst in 2008. Multiple attempts over the years to develop the property were shut down. Tax issues and funding mostly. In 2015, back taxes had risen over $500,000 and the structure sat wasted.

Old Reid’s story makes us sad and curious about Richmond. The town sits right near Route 40, the National Road, and now I-70. It was historically a major stop for travelers. But now, it feels small and lonely. We search, and immediately we learn of a humungous natural gas explosion on April 6, 1968. One third of Richmond’s downtown burned. 41 people were killed and 150 were injured. The fire hit Richmond’s economy hard. In an attempt by the town to bring business, they built a promenade in 1972. This model was unsuccessful and in 1997 was returned to car traffic. The same year, Route 40 was re-routed to bypass the downtown and like most other small towns that are bypassed, the people stopped coming.

That night it is hot, and we sleep in the back of the Jeep with the hatch open. Trucks barrel past every so often, on the way to some place with people. Lots of people who needs lots of things.

We wake up the next day, bug-bitten and happy, now we are traveling. I cook us oatmeal and coffee on the camp stove as Sam packs up. Rolling out of the campground, we aim dead-west on I-70, still so much of the U.S. to cross before sleep.

THE MIDDLE

Sunflowers, Nebraska

Lincoln Highway, Nebraska

Davenport, Urbandale, Anita, Lexington; we drive through town after town. We take the Lincoln Highway through most of Nebraska, first automobile road across the U.S. It connected parts of the Mormon and Cherokee Trails, the Pony Express, and the infamous Donner pass. It was so early that when looking it up, I found an old highway guide for the road. It said of the highway, “The recommended equipment [for traveling this road] includes chains, shovel, axe, jacks, tire casings, and inner tubes.” This is the gear we take when we are off-roading now.

We follow old wagon ruts across the plains and come through countless little municipalities. All of them have a water tower, a grain silo or two, a solitary stoplight, a glib post office, and of course, a sign containing the town’s name and population. Some of them only in the double digits. After going the two or three blocks that town lasts, there is a matching sign that says, “Thanks for Visiting Scenic fill-in-the-blank.”

CORN. SOY. GRAIN. 3 hours feels like a short jump up the road to me now. CORN. SOY. Sunflowers. Wait. Sunflowers. “Stop the car!” We stop and I crouch down among them. Their sweet faces. So many of them, they roll off with the horizon. Little yellow heads stick up proud out of all the green. Lovelies.

Each intersection is a four-way and grid-like. The roads lay flat, two crossed boards in the grass.

Torrington, Sheridan, Greybull, Cody. All small towns in Wyoming. The signs at the edge of town now include elevation. Yellowstone—people, Jackson—money, Pinedale—tourists. We put the miles down. Pace—nonstop.

Flaming Gorge Lake, Wyoming

Finally, it slows. We turn our Jeep down a backroad towards a dune field way out on some BLM land. Killpecker Dunes. What a name. The road is wash-boarded, we bounce around in our seats. There are old rail-grades shooting out into the desert. Sam drives through a lot of soft sand. Panic nearly sets in until he digs into the throttle and pulls us out the other side.

Dunes. Beautiful and speckled with wild flowers. There is a watering hole deep in a bowl of sand. Critters gather around it. Pronghorns stand on the smooth peaks. We are alone with the animals except for a set of tracks from some piece of large equipment leading further into the dunes. This isn’t a park. It just sits out here, mostly unknown. Trains used to push through the valley near them, shaking each grain. Not now, now it is just the locals and a few travelers, curious and brave enough to journey out into the wild west. Just us and these dunes.

We head southeast toward Flaming Gorge, following more ruts from some old trail. Turning towards the park, our road is paved and fast. We drive into an incredible canyon, the layers of stone exposed on spires above us. The road winds and we see a deep dry wash forming beside us. Storm clouds roll around on the horizon. We talk about water, the catastrophic force. It can rage. I have watched the Weather Channel’s radical and incendiary accounts of the flash floods. I know they are serious, but I also know that most of the people caught in the rushing water did not heed the warnings.

I drive fast on the paved road. We reach the lake that fills Flaming Gorge. It is stunning. Our road turns to follow the shoreline and immediately the pavement ends, and the bentonite begins. To backtrack would be a very long way. Even with the rain coming, we press on. Nerves make my shoulders stiff as I steer us up a drainage away from the gorge. A wash parallels the road and dark clouds hang on my rearview mirror.

Coming into a big flat, Sam asks me to stop the Jeep. “Do you see those buildings out there?” I use my camera to zoom in and see old ranch sheds and barns, their roofs folding in on themselves. The wash is deep here, 15-foot walls on either side. It sits between us and the structures. Knowing the stories, Sam and I get back in the Jeep and we drive away from that place. We leave those buildings there, just like their owners and the park service and all the other folks that stayed on this side of the wash.

We make camp in Flaming Gorge on the edge of a cliff face. There are big, wild walls of orange rock, momma and baby moose, and then, there is the once forgotten Swett Ranch. We hear stories about the former owners, Oscar and Emma. They sound flawless. We sneak away from their increbible homestead and into Dinosaur National Monument where we learn about another pioneer. Miss Josie Bassett was her name and her perfect cottage in the desert is the stuff dreams are made of, abandoned as well.

Abandoned Ranch. Flaming Gorge NRA

THE ANCIENTS

Cliff Palace - Mesa Verde National Park

Pictographs, Canyon Pintado

We drive southeast and stop in at a little visitor’s center just across the Colorado border. Some sweet older ladies are working and suggest that we run south through Canyon Pintado, or painted canyon. This canyon is famous for having an impressive number of petroglyphs and pictographs left here by the Fremont peoples.

Of course, we go. We follow our brochure guide and stop at one of the listed sites. Up a small trail and not more than 100 feet off the highway, there they are. Shapes of corn and strange men look at us from the orange stone. We take pictures. I wonder how many people drive by these and never stop, never have any idea of what they are passing.

We climb back in the Jeep and go a few more miles to the next stop on the guide. This stop is called “Waving Hands,” and when we walk up to the wall we know why. There are two brilliant white hands planted firmly on the rock. I don’t know why someone left them here. Maybe it was a symbol of something else. Maybe something like our “Don’t Walk” signs. But standing here looking at them, I am overcome by a feeling of connectedness. Like that person, over 800 years ago, traced their own hands onto that rock knowing that someone, me or anyone else, would look at it and know they were saying hello.

Around the corner from the hands is a large man painted on the wall. Our brochure calls him “The Guardian.” All ideas of what significance this little guy might have feel like pure speculation.

We go to Moab and Arches and Dead Horse Point. Then we turn toward Mesa Verde National Park, the place with the cliff dwellings. We arrive late at night. The parking lot of the camping services station is empty, the gates into the park have no attendants, the street lights around the lot are not on, and the fluorescents from the laundry mat shine in bright blue beams across the asphalt. The place looks tired.

Doors, Mesa Verde

We drive to our campground and it is completely empty. We make the whole loop. There is no one, not a single person, not a campfire light shining through the trees. No signs of life. I am creeped out and ask Sam to walk me to the bathroom. There are signs on the building warning about bear and mountain lions. Thick grass surrounds each site and shrubby trees make me claustrophobic. I feel like there are mountain lions all around us. We don’t eat and I ratchet-strap our cooler to the picnic table, hopeful that will ward off the critters.

We wake up and drive to the visitor’s center to get tickets. I choose the Balcony House tour. It is the most challenging offered; ladders and cliff faces and tunnels. We learn all about the Ancestral Puebloans and their motivations for choosing these places. A 23-year drought meant trying to find water any and everywhere possible. Each of the cliff houses has a spring that trickles from the stone in the back of the alcove.

After our tour guide tells us a bit about the place, we descend off the top of the mesa down a steep set of stairs and wrap around to a 32-foot ladder. I climb up and over the stone wall. I look out across the valley. Sunshine bathes the trees below us. I go through a tunnel and into the main living area, the people in the tour wander around. I imagine getting to live here. Flowers and herbs would hang from the yellow-orange sandstone stacked walls. Woven rugs would warm up the living areas. Perfect.

We finish the tour and go looking for more. The top of the mesa is covered with old, excavated pueblos. We walk through them, they are people-shaped. I feel like I could move in right now; put up some billowy white curtains and call it home.

The Guardian

Sam picks us out a twilight photography tour of Cliff Palace. It is the darling of the park, the must-see. We meet at 6:45, the sun is floating around on the horizon. There are only 15 people allowed on this tour. We follow our guide through some deep slots and come around the corner to a huge space, ruins running the full length of the alcove. I look into the deep shadows and see structures as far back as the light allows. The guide tells us we can wander freely. “If you have any questions I am excited to help answer them, but this is your time, spend it how you wish.” With an odd trepidation we all tiptoe into the palace.

This place is unbelievably massive. I picture my entire small town back in West Virginia living here. It feels empty with only 15 people filling its expanse. Lonely. I walk up to a tower and peak inside its door. I turn my head to look up, light comes in windows from high above. The beams that used to support floors are still suspended by the stone. Sturdy and ancient.

Why the people left this place is a deep mystery but most of the evidence points to a slew of instigators. The Great Drought was the first. 23 years without rain. Think about that. Not a drop fell for over 2 decades. The second is that of impending violence. The Apache, Navajo, and Anasazi were all migrating in the late 1200s. The larger and less easily defined theory is that of an ideological shift that caused the flight. William D. Lipe, an archeologist from Washington State University says that it “was a time of substantial social, political and religious ferment and experimentation.”

We leave Mesa Verde filled with a mild brand of dissatisfaction. It is an unbelievable place and spending some time there, we understand quickly that whatever the reason, it had to be immense to feel that the only option was to leave.

DEAD EAST

House, Colorado

Colorado is beautiful. I am certain anyone who has ever been will not argue. Even in August, snow-covered peaks stand high above the grassy valleys. Great Sand Dunes National Park is our next stop. We cross the San Juan Mountains, our Jeep moseys up the paved switchbacks, 40 miles per hour and heater cranked to keep the engine cool.

Coming down the other side we pass sleepy ranch entrance gates, one after the next. We fall into a massive valley, 50 miles across. I look out and in the hazy distance, I see a small dune field. The wind at our back, we drive for a long time; the dunes our guide star. We come to an intersection and a tiny town called Mosca. About 5 dainty houses and a firehall sit perched. We turn right, away from them. A white house sits like an empty bullet casing. It is missing its windows and its trim, the parts that make it sweet and enchanting. It hauntingly resides over the sand dunes.

We drive another 20 minutes. We see the dunes, they are bigger than I could ever imagine. A thunder storm rolls in and we eat dinner in the Jeep. We run into some friends from back home and sit around a fire for the first time on our trip. Community.

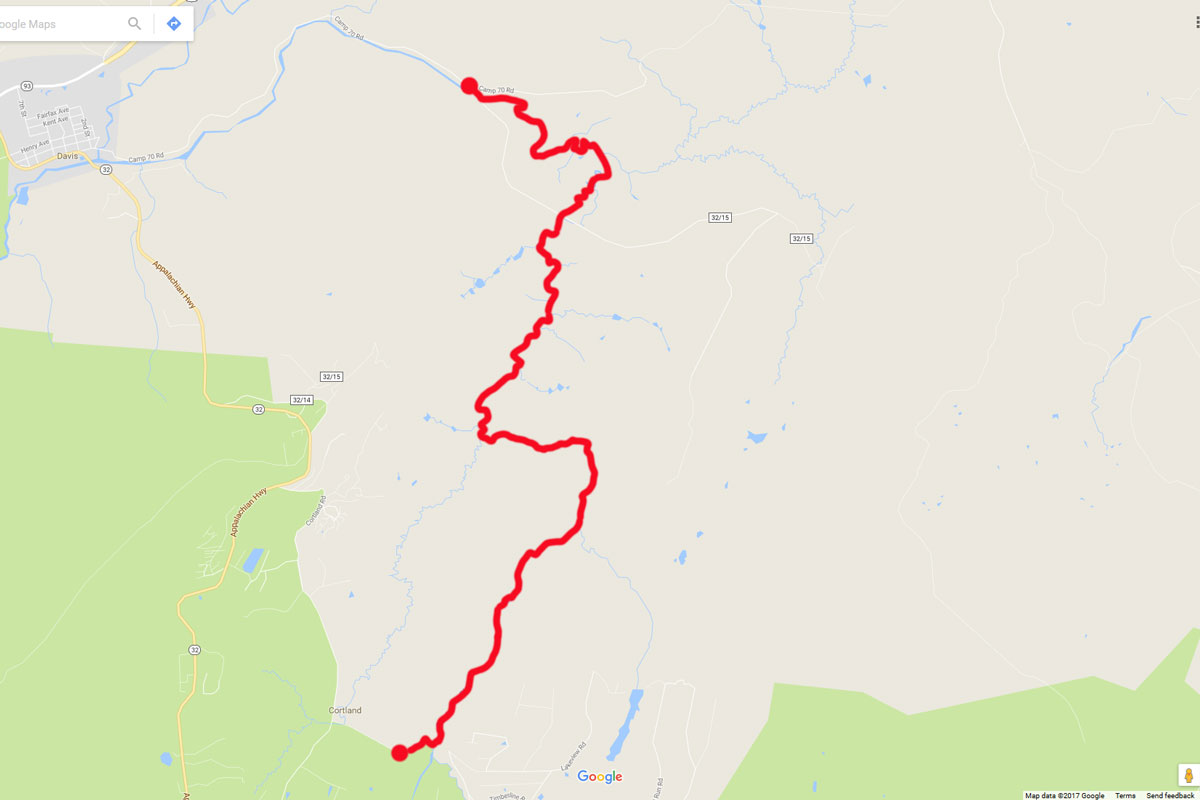

The next day there is a lot of driving. We pass through Raton, New Mexico, a little town old as sin. We eat the best Mexican food of our lives and go to ANOTHER visitor’s center. I find pamphlets for the Santa Fe and Spanish Trails. We try to follow them. More wagon ruts appear along the road. Small towns forever. Maxwell, Springer, Mills. We drive into the Kiowa National Grasslands looking for a ghost town Sam read about, Mills Canyon. Once again, weather is looming, and we turn back.

Out-driving the weather, we stop and look out across the big, horizontal place; darks clouds way in the distance. Flatness a West Virginian can never quite get used to.

We drive through Roy, New Mexico. It is small and feels very old. Or like it is trying to feel very old. We go through Solano, Mosquero, Logan, and Porter before we finally drive across the Texas border. 70 miles to Amarillo, our stop for the night. We hit I-40 and cruise on a 4-lane for the first time in what feels like a month. The miles tick down. We start seeing Old Route 66 signage. It is dark when we roll into town. It looks just like a lot of other medium-sized towns in the country. A few more cowboy boots is the biggest difference I see.

At a restaurant in Amarillo, we learn of Hurricane Harvey. We were supposed to go right through its path. Nope. We change course and follow Old 66 through Oklahoma and then head east across Missouri. Small towns. We stop in the Mark Twain National Forest to camp. It is desolate. We find a place that we think is distributed camping and drink until we can sleep, music blaring.

Mills Canyon, New Mexico

FAMILIAR WITH THE APOCALYPSE

Confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio River (Ohio River left, Mississippi River right)

Over a Mcdonald’s breakfast the next morning we discuss our route for the day. Hotel in Lexington, Kentucky or camping somewhere in the eastern part of the state? Camping. Looking at the map we ponder where we should cross the Big Muddy; I google Mississippi River towns. Cairo, Illinois pops up on Atlas Obscura. Pronounced care-oh. The headline reads, “Abandoned Town of Cairo, Illinois. A once-booming Mississippi River port town has transformed into an eerie, mostly abandoned ghost town.” Cairo is at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.

Map of Cairo, Illinois, CA 1885. Library of Congress

Sam reads to me as I drive. “The town has mostly been abandoned because of its economic desperation, though its history of racial tension certainly didn’t help.” He looks for other sources and reads accounts of packs of wild dogs running the streets, police murders of young black men, and the downtown looking like a scene out of The Walking Dead. Our curiosity is insatiable, we have to see this place for ourselves.

We drive pot-hole ridden two-lane roads and just before town we stop at a little park where the big rivers meet, Fort Defiance State Park. Sweeping, pretty trees mark the way and we start to see water peeking through on either side of us. The land comes to a point and there is a tall observation deck roosted on the grass above the water. We climb it and look out at the expanse. Everything in the park is a little run-down but otherwise it is a pleasant spot. We eat lunch. The barges going by make the water rise and fall near our feet.

Sam packs the camp kitchen back into the hatch while I grab the axe off the side of the Jeep and put it within reach. Packs of wild dogs are nothing to be messed with. The final push into Cairo reminds me of riding my bike down the rail-trail along the Monongahela in Morgantown. Fields. Trees. Floodplains. Evidence of high water.

Cairo, Illinois. Jonathunder, GDFL/1.2, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GEMblockCairoIL.jpg

Coming into town, there are people walking down the sidewalks, a lot of empty storefronts, people relaxing on their porches and in their yards, and a couple of open restaurants. My first impression of Cairo is that it looks a lot like every small town in West Virginia, only bigger. It might have boomed and is now declining but there are still people living here. There are still businesses running. This is not apocalyptic, this is what rural America looks like.

A disconnect: how is it this place has such a bad rap? How is it that so many people came here and had the same reaction?

Then we realize. Cairo isn’t scary or strange to us. The economic damage and the rundown buildings are our norm. Main streets with only 1 or 2 restaurants feel like enough. There is nothing Walking Dead about this place to us. We are from this town, maybe not this exact town but a town that feels and looks just like this one.

Then we understand. The economic gap and the perception of poverty are much wider than we each thought. The people online, the people who call this place abandoned. They don’t know the towns we know. Here is the moral of the story: they don’t know the poverty we know. Poverty isn’t scary when you know what it looks like. The desperate people, we know them. They are our families, our friends. We have been desperate, and it lit a fire inside of us. Desperation is scary because desperate people will do whatever it takes and sometimes, whatever it takes is unspeakable. The hustle.

We leave Cairo and drive most of the way across Kentucky in a daze. White rail fences run along the road for miles. Green pastures stare at us from the other side and Harvey’s impending weather makes for never-ending overcast. Dreary.

LAST STOP

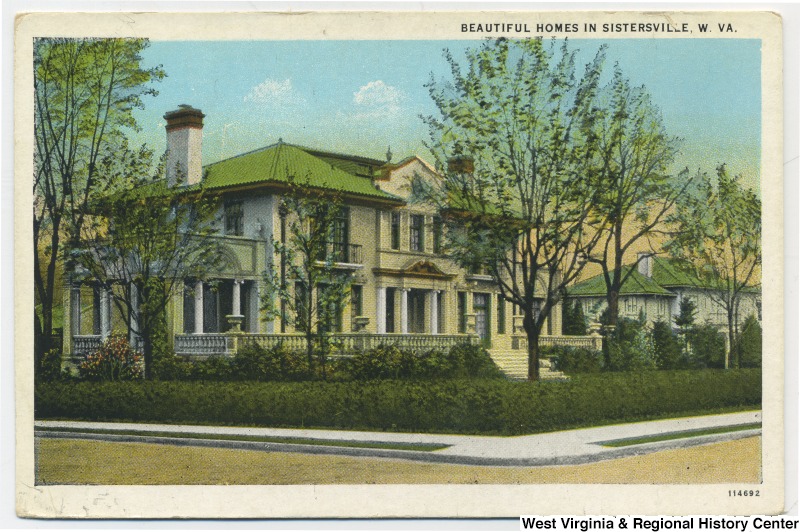

Billion Dollar Coalfield, Williamson, West Virginia

After a heavy day, we camp in Eastern Kentucky at a spot called Twin Knobs Campground. We sit at the picnic table and talk about home and traveling and how we could both just keep going. Sleep grips us and we wake up the next morning groggy, the romance of our trip already beginning to fade. We head east toward the wild and wonderful.

Mingo County, West Virginia. Home.

Hatfield Street, Matewan, West Virginia

We cross the border hungry and aim for a little hotdog shop in Williamson called Tunnel Drive-In. This place is over 30 years old. The food is alright but the vibe is good. Kitschy and American.

This is my first time in Mingo County but the things I’ve heard don’t paint a pretty picture. Drugs, filth, and lack of education. I’ve read entire books about how the man in these parts has gone to great lengths to keep the poor people poor. Murder and corruption.

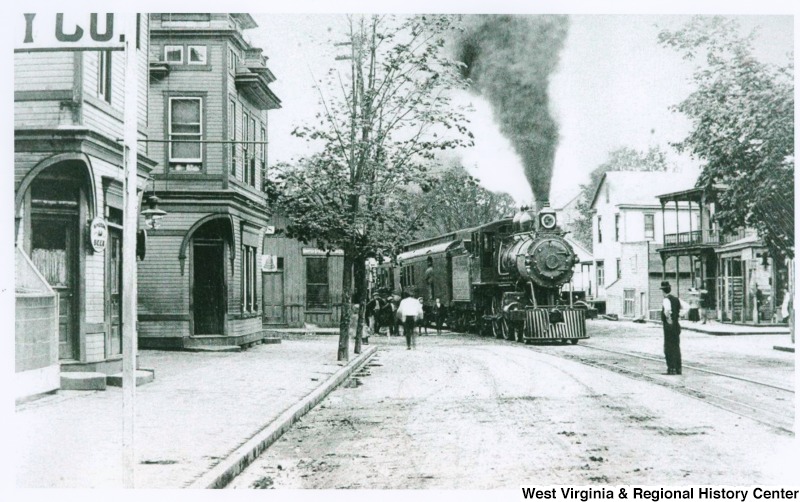

Now, it is quiet and pretty in this place. There are small neighborhoods, a big ole railyard, and a newly-built, consolidated school for the county. It is a lot like my home county; trains rumbling through, old buildings, and perpetually sleepy. It feels like many of the places we saw stippled across the U.S.

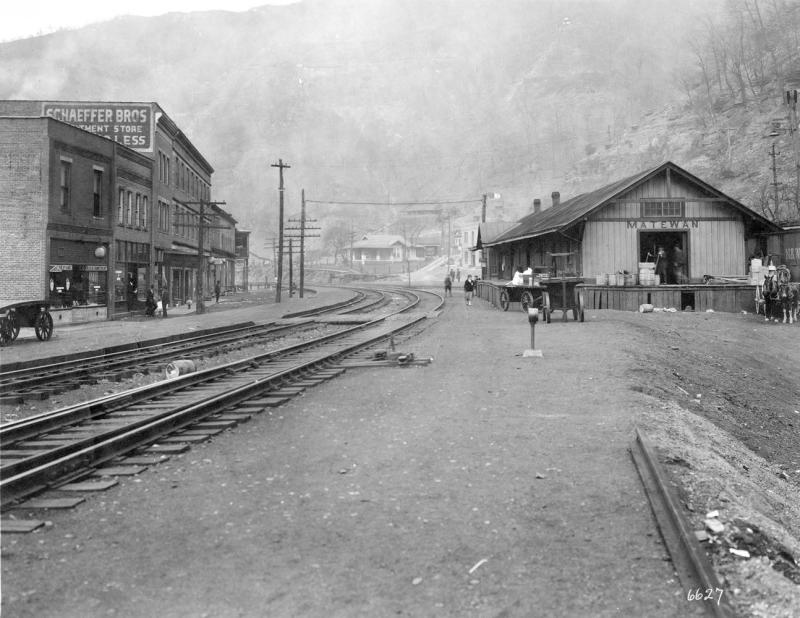

We dig into our West Virginia Atlas and find some gravel roads to run. We go to Matewan, the scene for the 1920 shootout between the coal miners and the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency. Town is deserted. The streets lack any signs of life. No vehicles, no people, no food-smells, nothing. We find a sign to tell us about the massacre. Bullet holes still speckle some of the buildings. There is a museum but it is locked up tight. We amble down the street.

Matewan N&W Station, http://www.wvexp.com/index.php/Matewan,_West_Virginia

At the end of town we find the UMWA(United Mine Workers of America) union hall. One lonely truck sits in the gravel lot. A man comes out of the building, he waves and asks, “What’er yall doin in these parts?” We get this question a lot and today we are the only people in town to ask. Just us and this retired miner and Vietnam vet. Sam says, “We are from the central part of the state. Just exploring and have always wanted to get down here.” The man hears Sam’s accent and seems appeased. “Not much ‘ere,” the man says. We hear that a lot too.

We chat with the man for a while and he heads out of town. I follow Sam along the railroad tracks back to the Jeep. I see that the buildings were designed for their storefronts to cater to the people getting off the train way-back-when. They don’t stop here anymore. Boards cover some of the windows, others boast a thick layer of dust. The ornate facades hang onto the stone and brick above us. We hear a whistle blow a-little-ways in the distance and the ground growls under our feet. The buildings vibrate. I feel a deep desire to buy these creaky old souls, save the structures before they can’t be brought back.

There are banks and businesses that look like they just closed yesterday. Modern and ordinary except that they are empty. People-shaped. Right next to them are spots that look long-forgotten; floors caving in and tin ceiling tiles hanging by a thread. It feels like people have been leaving this place as long as they’ve been coming. The die-back.

This blog is dedicated to the following:

The people, the educated, the blue-collar, the fed-up, the fierce, the discouraged, the majority, the bold, the underestimated, the laid-off, the salt-of-the-earth, the hungry, the wise, the down-home, the back-40 livin’, the final few, the south-bound, the west-bound, the north-bound, and the east-bound. The ones doing whatever it takes.